Russell A. Hart, Guderian: Panzer Pioneer or Myth Maker?; 144 pp (paperback); Potomac Books, Washington; 2006; ISBN10: 1574888102; ISBN13: 9781574888102

Russell Hart is Associate Professor of History at Hawai’i Pacific University in Honolulu. Hart is the author of Clash of Arms: How the Allies Won in Normandy (2001) and co-author of Weapons and Tactics of the Waffen-SS (1999); Panzer: The Illustrated History of Germany’s Armored Forces in WWII (1999); The German Soldier in WWII (2000), and German Tanks of WWII (2007).

We already knew that Sir Basil Liddell Hart distorted his autobiography to make it appear as if his ideas on armoured warfare were adopted by the German and Allied armies in World War Two. Now Heinz Guderian is in for the same treatment. According to Russell Hart, if one man should be regarded as the father of German armoured forces and maneuver warfare in World War II it would have to be General Oswald Lutz.

Oswald who?

Lutz was the first and probably the most influential member of a set of German armoured warfare pioneers in the 1920’s, along with WWI tank commander Lieutenant Ernst von Volckheim, the Inspector General of Motor Transport Troops (1926-31) Colonel Alfred von Vollard-Bockelberg, Austrian Major Ludwig Ritter von Eimannsberger and – yes – motorised troop inspector and later cavalry General and Inspector Geneal of Armoured Troops Heinz Wilhelm Guderian (1888-1954), author of Achtung! Panzer! (1937).

Achtung! Panzer! has long been regarded as the seminal text on German Blitzkrieg tactics. It probably was, but Guderian wrote it on an order from Lutz, who was the Head of Mechanized Forces since November 1935 and the most visionary of the lot. Guderian’s book owes a lot to Ludwig Ritter von Eimannsberger’s 1933 study Der Kampfwagenkrieg (“The Tank War”).

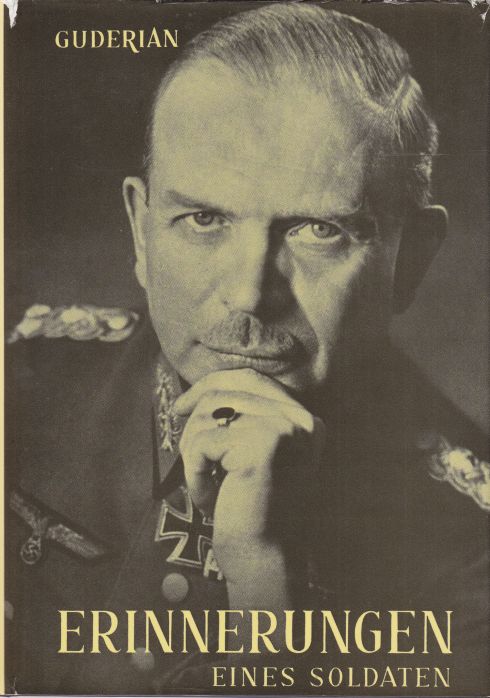

Lutz died in his bed in 1944 after an illness, and so did Eimannsberger a year later. Other pioneers perished at the front. Schneller Heinz (‘fast Heinz’) who survived both the war and the Neurenberg trial was able to create his own legend with Erinnerungen eines Soldaten (Memories of a Soldier), published in 1950, in which he studiously ignored or belittled the contributions of others, sang his own praises as a theoretician and field general, and conveniently passed over his profound sympathy for Hitler and the National Socialist worldview.

The book was translated and published as Panzer Leader by Da Capo Press in New York in 1952 and became one of the most widely read accounts of World War II. Sadly most of Guderian’s biographers (such as John Keegan, Kenneth Macksey, Karl Walde and Dermot Bradley) have accepted too much of this self-serving and distorted memoir at face value. German armoured warfare and the Blitzkrieg neither originated nor reached their apogee with Guderian. The most that can be said in his favour is that he was a determined if reckless panzer leader.

The book was translated and published as Panzer Leader by Da Capo Press in New York in 1952 and became one of the most widely read accounts of World War II. Sadly most of Guderian’s biographers (such as John Keegan, Kenneth Macksey, Karl Walde and Dermot Bradley) have accepted too much of this self-serving and distorted memoir at face value. German armoured warfare and the Blitzkrieg neither originated nor reached their apogee with Guderian. The most that can be said in his favour is that he was a determined if reckless panzer leader.

Guderian wasn’t the unstoppable innovator he pretended to be and the Oberkommando des Heeres wasn’t as ossified as he portrayed it, but the fact of the matter is that mavericks like Heinz Brausewind (‘Heinz Whirlwind’, another of his many nicknames) were needed to shake up the lower echelons of the traumatised, inward-looking post-war German army and introduce them to new technologies and concepts. Even Hitler was personally impressed with Guderian’s can-do attitude, epitomised in his credo “Klotzen, nicht kleckern!” (“Don’t mess around, whack!”). He despised his superiors, but vigourously protected his own subordinates from outside criticism. On top of that Guderian tirelessly and consistently led from the front, earning the respect of his men at every turn of every operation he commanded.

The official German history of the May 1940 campaign in the West (1) has exploded several myths concerning German Blitzkrieg tactics and planning: both the Germans and the Franco-British Allies had sound battle plans, but the former were superior when it came to improvisation. When it comes to the origins of the German combined-arms tactics, Hart emphasises that they were the outcome of teamwork. Guderian was merely the most fanatic, propagating the purist (and fundamentally doomed) view that armoured columns by themselves could decide modern wars, even when operating without artillery, infantry and air support. His view was rejected at an early stage and never implemented, but it enabled him to inspire his men to uncommon feats of courage and persistence. Since he was also insufferably arrogant and myopic most of his accomplishments in the field were undone by his tendency to find fault (and quarrel incessantly) with his superiors, and by his disregard for the operational needs of branches other than his beloved Panzer. Against the odds and often against the orders of his superiors and even of Hitler himself, Guderian set out to prove his view in the field and failed, but not without having had his moments of brilliance in France, Poland and Russia.

Hart convincingly argues that the true origins of German maneuver tactics are to be found in the horrendously wasteful trench warfare of WWI and in the Treaty of Versailles. As a staff officer during the Great War Guderian had avoided the trenches and “used this opportunity to contemplate potential means of preventing a future recurrence of static warfare”. He was not alone in this, as witnessed by the fact that the new German commander-in-chief Hans von Seeckt began to develop plans for combined-arms warfare in the early 1920’s.

‘Versailles’ in turn, by constraining the German post-war military to 100.000 ground troops, acted as an additional driving force for tactical innovation. Says Hart:

Too weak to defend itself against its enemies, the Reichswehr was psychologically motivated to do things that other armies were not – to seek every advantage and to innovate. Thus it resumed annual maneuvers as early as 1922 and from 1923 began holding exercises with hypothetical and improvised motorized forces.

Guderian was a lowly Inspector of Transport Troops at the time and even though he propagated a blind faith in the capacity of armoured spearheads to decide any future war, Hart concludes with some understatement that “the Reichswehr did not look for his lead in these efforts”. Besides, as Hart duly notes, the opponents of forced mechanisation had sound reasons as well. Their objections were grounded in the selfsame weak position of Germany, particularly its limited resources in oil, which would leave it dependent on foreign imports and vulnerable in time of war. Both Hitler and Guderian, Hart argues, ignored this reality at their peril.

Hart’s Guderian is not a ground-breaking book. It relies solely on the original scholarship of others such as Robert Citino’s The Path to Blitzkrieg (1987), Florian Rothbrust’s Guderian’s XIX Corps and the Battle for France (1990), James Corum’s The Road to Blitzkrieg (1992), and Heinrich Schwendemann’s article Strategie der Selbstvernichtung. Die Wehrmachtsführung im “Endkampf” um das “Dritte Reich” in: Rolf-Dieter Müller, Volkmann H.E. (eds), Die Wehrmacht. Mythos und Realität (1999). Nor is it well written; it suffers from bad English, bad composition and bad editing.

In order to compensate for his lack of originality Hart does a complete hatchet job on his subject by downsizing Guderian’s personality at every turn of his career and highlighting his blind fanaticism, a character trait that wasn’t exactly in short supply in the post-Prussian army of the Weimar Republic. Guderian was a crook alright, arrogant, self-possessed, ruthless and much closer to the Nazi regime and to Hitler personally than he claimed to have been in his post-war memoir. He was also a fine leader of men and a daring tactician.

And was Guderian really a disastrously short-sighted strategist as Hart claims? Let us consider the author’s strongest argument, which is that Guderian’s view of the next stage of of Operation Barbarossa in the spring of 1942 was fundamentally flawed:

Nowhere did Guderian more clearly reveal his strategic myopia than in his stubborn belief that the capture of Moscow would collapse communist rule and end the war in the East.

In reality Guderian’s view was shared by the majority of senior German military leaders at the time who advised Hitler to take Moscow first, and for good reason: the bulk of the Soviet forces were concentrated there and their encirclement and loss would be a devastating political blow to the government. Hitler made the decision to turn to the Crimea, the Don Steppe and the Caucasus entirely on his own. In fact Stalin himself fully expected the Germans to strike at Moscow for the reasons mentioned. When a small German aircraft carrying detailed plans of the southeasterly thrust crashed behind Soviet lines in June, 1942, Stalin discarded it as a clumsy piece of disinformation. (2)

Even with perfect hindsight one is struck by the audacity and imagination of the early German Panzer troops whose equipment – contrary to Blitzkrieg lore – was far from superior to French or Russian tanks. Their rickety PzKpfw I’s and II’s became cannon fodder as soon as they stopped moving, something Guderian understood better than most of his superiors.

Fortunately we can now make fun of them, as per the tv series ‘Allo ‘allo in which the blatantly effeminate Lieutenant Hubert Gruber invites his prospective male lovers to a ride in “my little tank”. On a more serious note, one is reminded of Jean-Paul Sartre’s topical remark when he was given a guided tour of the Stalingrad rubble in the 1950’s. Time and again the philosopher was heard to murmur “incredible, incredible!” When his Communist tour guide sought to capitalise on his amazement – “Isn’t it incredible that the Nazi’s wrought so much destruction?” – Sartre countered: “No no, it’s incredible that they managed to get this far!”

(1) Karl-Heinz Frieser, Blitzkrieg-Legende. Der Westfeldzug 1940, München, 1995

(2) Richard Overy, Why the Allies Won, London, 2006